Home / Hospitals Sometimes Lose Money by Using a Supply Buying Group

Hospitals Sometimes Lose Money by Using a Supply Buying Group

![]()

April 30, 2002

Medicine's Middlemen

Hospitals Sometimes Lose Money by Using a Supply Buying Group

By Mary Williams Walsh and Barry Meier

Two groups that dominate the purchasing of medical products for about half the nation's nonprofit hospitals have long said they exist to save money, pooling the influence of thousands of hospitals to negotiate a good price on the best products.

But some hospitals are finding otherwise. They have learned that they can do better on their own, and are now raising questions about the need for the huge buying groups, which negotiated contracts last year for $34 billion in supplies.

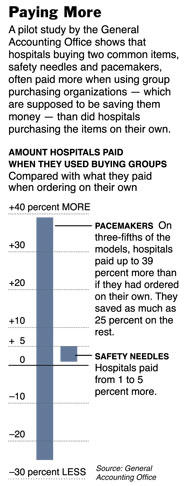

A new, preliminary study by the research arm of Congress, the General Accounting Office, is also challenging the buying groups' claims.

In the study, a copy of which was obtained by The New York Times, the G.A.O. found that using a big buying group "did not guarantee that the hospital saved money." In fact, prices negotiated by buying groups "were often higher than prices paid by hospitals negotiating directly with vendors" — in some cases "at least 25 percent higher," the G.A.O. said.

At issue are hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars in annual health care costs, much of it paid indirectly by taxpayers through programs like Medicare and Medicaid and by private insurers.

The G.A.O. report is to be presented today at the first Congressional hearing on the operations of these buying groups. The hearing will be held by the antitrust subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee. The subcommittee is headed by Herb Kohl, Democrat of Wisconsin.

The report comes a day after one of the largest buying groups, Premier Inc., took out a full-page ad in Roll Call, a newspaper covering Capitol Hill.

In the ad, Premier took credit for "holding down the costs of health care for American businesses, taxpayers, and consumers."

The G.A.O. cautioned that its initial report was limited in scope and said it planned a broader inquiry. Government auditors surveyed hospitals in only one city for the prices they paid for two categories of products: pacemakers and hypodermic needles with safety features to prevent accidental sticks. Some of the hospitals surveyed bought such products through contracts negotiated by buying groups, while others made their own deals.

Officials of the two biggest buying groups, Premier and Novation, which together negotiate contracts on behalf of about half of nonprofit hospitals, said they had not seen the study. Told of its findings, they disputed its methods and results.

Jody Hatcher, vice president for marketing for Novation, based in Irving, Tex., said the findings were skewed because the study looked at only two products rather than a wider range of supplies.

"I think you have a flawed study," he said. He and Premier officials said that if hospitals could really save money on their own they would be leaving buying groups in droves.

But the G.A.O. survey, even with its limitations, adds to the growing debate about whether groups like Premier and Novation really lower the cost of medical products for the hospitals that own the groups or buy through them. Some hospital executives said in interviews that the groups did save them money, while others said they saved many millions of dollars by going it alone.

Unlike other purchasing agents, the groups buying supplies for hospitals are financed by the products' manufacturers and distributors, which pay the groups' fees based on a percentage of sales. That arrangement has led to questions about whose interests the buying groups really serve.

Hospitals that have broken away from buying groups cite several reasons for getting lower prices than they would have through the groups. One is the ability to negotiate with a larger number of manufacturers. Another is shorter contracts that allow hospitals to take advantage of falling prices. A third is that manufacturers freed of the need to pay fees to the buying groups will pass on the savings to hospitals.

Two years ago, for example, executives of a 10-hospital chain in Iowa decided to end their relationship with Premier. Officials of the Iowa Health System said they found that each time they renegotiated a supply contract, they beat the buying group's price by 12 percent to 14 percent. They are already saving $7 million a year, and expect that figure to grow as more contracts are redone.

Duncan Gallagher, executive vice president of Iowa Health, said that for years the common wisdom was that hospitals that tried to buy on their own would pay more. He expects that his system may eventually save 30 percent to 40 percent.

"The people who are saying it is impossible are wrong," Mr. Gallagher said.

Nicholas C. Toscano, who oversees purchasing for the Virtua Health chain of hospitals in New Jersey, said administrative fees and incentive payments that suppliers pay buying groups for handling their contracts can also raise prices for hospitals.

Virtua studied the benefits and costs of buying through a large group and decided it could do better on its own. "If the administrative fee is 3 percent, we normally save, right off the top, 3 percent," Mr. Toscano said.

Another factor driving up buying-group prices, Mr. Toscano said, is contract language that allows manufacturers to lock in price increases over several years, even at times when the price of the products is falling on the open market.

He said that by writing contracts for shorter periods, Virtua has found opportunities to take advantage of falling prices.

But Premier officials say they also renegotiate prices on contracts and some hospitals add that the size of the big buying groups can command better prices.

"It is very simple economics," said Keith Callahan, a vice president of Catholic Healthcare West, a large hospital system based in San Francisco that belongs to Premier.

The G.A.O. review is a rare effort to examine independently the impact of buying groups on hospital prices.

In the case of pacemakers, it found that while some hospitals using buying-group contracts got better prices on some models, they got much worse prices on others. The G.A.O. also found that big groups like Premier and Novation often did not get better prices for the products under study than did smaller purchasing groups.

"This lack of consistent price savings is contrary to what would be expected for large" buying groups, the study found.

The survey also found that large hospitals — those with more than 500 beds — often got lower prices on their own than by using a buying group. By contrast, small and medium hospitals tended to do better using a buying group. But even in that group, government auditors found, the experience of hospitals differed.